The oldest of five children, Thandiwe in Zambia has always looked after her younger siblings. When the village borehole broke down, she had to fetch water from the river, and her family couldn’t wash as often. Thandiwe noticed some of her siblings had itchy, red eyes. Soon, she developed the same eye condition. Her left eye swelled and her eyelid turned inward, causing unbearable pain as her eyelashes scratched her cornea. With no money or access to a doctor, her eye became worse and worse until she lost vision in it entirely.

Priya in Nepal can’t remember when she first started having trouble seeing, but her vision kept deteriorating until one day she fell and injured herself while climbing the steep trail leading from the village to her house. Figuring that blindness was an inevitable part of old age, she stayed at home, unable to visit friends and grandchildren. Eventually she couldn’t even reach the outhouse without assistance. She felt like a burden to her family.

Mary, in Kenya, loved school from her very first day in the classroom and dreamed of becoming a teacher someday. After she turned 13, she started having trouble reading the chalk board. She had to copy notes from her friends and couldn’t do her homework in the dim light at her house. Her grades began to slip. She asked her parents to take her to an eye doctor, but money was too tight because they were saving to send her brother to college. By age 15, Mary quit school and decided to get married, her hopes of teaching now crushed.

None of these characters are real, but they represent the millions of women and girls around the world who are living with avoidable vision loss and blindness. We hear stories like these every day.

The prevalence of vision loss is higher among women and girls than it is for men and boys; 55 per cent of people experiencing vision loss are female. And while there are some biological factors at play, the reasons for these discrepancies are largely social.

Why women and girls experience more vision impairment

Women live on average longer than men, and many conditions that rob people of their sight are associated with old age. This includes cataract, presbyopia, glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration. According to estimates, two-thirds of cataract blindness globally occurs in women.

Traditional gender roles are another factor, especially in some regions.

Women and girls are two to four times more likely than men and boys to get trachoma – the leading infectious cause of blindness worldwide. Trachoma is caused by bacteria that spreads through contact on hands and clothing. Small children are especially susceptible, and in turn, they often pass it on to their caretakers. Women and girls may also get infected from household cleaning and doing laundry.

Obstacles to eye health care access

The barriers to health care for women and girls vary widely from region to region, but there are trends that we can observe across the countries where we work. These include:

- Cost and lack of financial decision-making capacity: Men often control the family finances. Women are less likely to work outside the home, meaning that the men and boys in their family who earn an income are often prioritized for spending on treatment.

- Limited healthcare infrastructure: In some regions, particularly in rural areas, inadequate healthcare infrastructure makes it difficult for women and girls to access eye care. The cost or lack of public transportation to the nearest facilities can exacerbate this problem for many women and girls, as can the social taboos and safety risks presented by travelling alone.

- Family responsibilities: Running a household and taking care of family members, duties that often fall on women, can make it challenging for women to take the time they need to get eye care.

- Lack of information: Unequal access to education for women and girls contributes to lower literacy rates and educational levels, which make it more difficult for women to learn about a specific eye condition or find out where they can get it treated.

- Cultural stigmas: Cultural norms and stigmas surrounding health issues, particularly eye health, can dissuade women from getting help. These cultural barriers may result in delayed or avoided medical attention.

- Lack of female healthcare professionals: A shortage of female healthcare professionals in the eye care sector can create discomfort for women and girls, potentially discouraging them from seeking assistance.

Addressing these diverse challenges is crucial for breaking down the barriers that prevent women and girls from accessing essential eye health care services.

Working toward gender equality

Our approach, called the “Hospital-Based Community Eye Health Program Model,” is designed to address inequalities to accessing eye health care, starting at the village level.

Most of the community health workers trained by Operation Eyesight’s partner hospitals are women, which gives them the opportunity to become trusted leaders in their communities and helps them contribute to family finances. They also bring eye health screenings to people’s doorsteps, meaning that women and girls don’t need to travel to get primary eye care and referrals.

Additionally, we work with our partner hospitals to establish vision centres closer to the communities where we work, making it easier for everyone to access diagnosis and treatment. Our partner hospitals also provide safe transportation for patients – usually by bus – to the hospital so that they can get their surgeries without worrying about how they’ll get there.

Finally, by providing surgeries, eyeglasses and other treatments free of charge – or at a highly subsidized rate – we can decrease some of the financial barriers women and girls face. We strive to provide quality eye care services to everyone – regardless of gender, age, ability to pay or other personal circumstances.

Dismantling gender-related eye health myths in the foothills of the Himalayas

In the villages of the Udhampur block in Jammu region, vision problems are often seen as a sign of bad luck. A girl wearing glasses might be told she’ll never have a good marriage, and a baby’s bad eyesight might be blamed on past life sins. A girl with a squint could be seen as a curse for the whole family.

Those are some of the beliefs a recent pilot project took aim at.

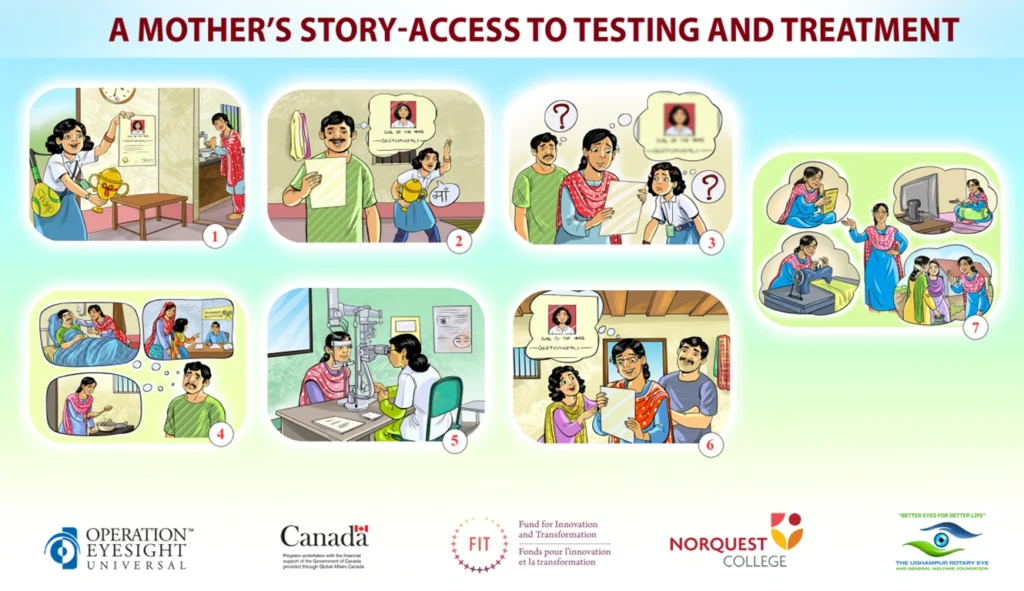

Created in partnership with NorQuest College and the Rotary Eye & ENT Hospital, the project provided services through a “Mobile Vision Centre” – a four-wheel-drive van staffed with an eye health team comprised mostly of women. The van roamed the area’s rugged roads, bringing primary eye care and education to people’s doorsteps.

More than 27,000 people received training pertaining to eye health myths during the project duration. A before-and-after survey that checked people’s attitudes and beliefs regarding eye health for girls and women showed dramatic differences after the intervention. With that success in mind, our teams are looking to implement strategies from the project throughout our programs.

Donate today to help us bring quality eye health care to more women and girls.